National Society Daughters of

The American Revolution, (NSDAR)

Commodore John Barry Chapter

Mrs. John Barry: “A Patriot in Her Own Right”

by Peg Pappelardo, CJB Historian 2019-2021

Sarah Austin was born 1754 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, British Colonial America, to Samuel Austin and Sarah Keen. Her ancestor, Joran Kyn (Keen as early as 1665), boarded the ship Fama from Stockholm in 1642, bound for the New World, “part of the Swedish colonization efforts in the Americas.” Joran joined the Swedish Colony “which held settlements on both sides of the Delaware Valley of New Jersey and Pennsylvania.” He settled at Upland, New Sweden (Chester, Pennsylvania), where for 25 years he held the position of Chief Proprietor of Land. Many of his fellow passengers from the ship Fama returned to Sweden.

Sarah’s mother was a widow and her father a widower when they married at Christ’s Church, Philadelphia in 1748. Sarah Keen’s parents were Jonas Keen and Sarah Dahlbo. Samuel Austin’s parents were John Austin and Jane Potts. The family “resided on the eastern portion of property inherited from John Austin on the north side of Mulberry St., where there were stores and a wharf on the river.” Samuel Austin, a joiner by occupation, “obtained a license to keep a ferry between Philadelphia and New Jersey in 1760 for a yearly rent of 30 pounds,” a venture passed down for successive generations. Sarah Austin was the youngest in her family. They affectionately called her ‘Sally’. Christiana Stille was the oldest sibling, a 1/2 sister from Sarah Keen’s first marriage, then came the Austin brothers, William and Isaac.

Although their parents were married at Christ’s Church, the family belonged to the Gloria Dei Church, known locally as ‘Old Swedes’ Church. Generations of Keen ancestors had worshiped and were buried there. “The congregation dates to 1677, five years before the founding of the city of Philadelphia, and the graveyard around the church to about the same time.” The building is still located in the Southwark neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at 929 South Water Street. It was built between 1698 and 1700, making it the oldest church in Pennsylvania and a designated National Historic Site.

The colonial Philadelphia of Sarah’s childhood was a bustling urban city of broad tree shaded streets, churches, mansions, horse drawn carriages, large brick and stone buildings, busy alleyways, warehouses, printed newspapers, the largest population of any colonial city and Benjamin Franklin. “The most important port in the mainland of the British Colony,” large British sanctioned ships crowded Philadelphia docks supporting British sanctioned maritime trade.

In 1765, the British Parliament’s Stamp Act caused a colonial uproar, which led to the formation of the Sons of Liberty and brought about the slogan “No taxation without representation.” Next came the Tea Act of 1773 which caused the Boston Tea Party and in December of 1773 the lesser known Philadelphia Tea Party in which “a British tea ship was intercepted by American colonists and forced to return its cargo to Great Britain.” From that point in history, “it was generally known that Philadelphia merchants were greater smugglers of tea than their Boston counterparts.” After 12 more British Parliament Acts intended to impose greater control over the colonies, a meeting was planned in Philadelphia of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies which was called The First Continental Congress 1774, followed by the creation of the Continental Association 1774, Petition to the King ratified 1774, Second Continental Congress 1775, Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms 1775, and The Declaration of Independence 1776.

Colonial life after the Declaration of Independence became a time of confusion and indecision for many. Going to war with their mother country, Britain being the main naval power in Europe, was a difficult choice to make. John Adams claimed that at the beginning of the war the country was divided into “1/3 Loyalists, 1/3 Patriots and 1/3 fence-sitters.” Many families were divided and friendships ended. In spite of the fact that Patriots were the majority in Philadelphia and that the city became the headquarters of the colonies, many Loyalist sympathizers and spies lurked within society and some families, disguised as fence-sitters.

By 1777, Sarah Austin was a 23 year old woman of independent means, as she inherited a portion of her father’s property on Arch Street. In the book The Descendants of Joran Kyn, it reports that Sarah joined a group of ladies of the Gloria Dei Church Congregation, who “under the direction of the Secretary of the Maritime Committee, she made a flag of ‘stars and stripes’ after the pattern adopted by Congress for the United States, June 14, 1777, and presented it to John Paul Jones, appointed the same day to command the Ranger, on which vessel he hoisted it, soon afterwards, at Portsmouth.”

The book also stated that, “On the 7th of July, 1777, Miss Austin became the second wife of John Barry, the renowned first Commodore of the United States Navy.”

An interesting historic note: “Betsy Ross was married for the second time in June 1777, this time to sea captain, Joseph Ashburn, in a ceremony performed at Old Swedes Church in Philadelphia” (Gloria Dei Church).

Sarah’s two brothers were active participants in the war. Brother Isaac, a watchmaker by trade, inherited the northeast corner of his father’s property on Arch and Water Streets. Isaac served as Ensign with a volunteer military association called the Second Battalion of Philadelphia Associators. Due to the fact there was no Pennsylvania mandatory military service rule in 1775, “activist elements among Pennsylvania’s population organized local volunteer ‘associations’. When General Washington asked for the middle Atlantic states to provide additional reinforcements willing to serve for six months duty in 1776, the Associator units were tapped as a manpower pool.”

Brother William, being the oldest son, inherited the eastern portion of Samuel Austin’s property on Mulberry Street, including the river front, therefore Austin’s New Jersey Ferry. In an August 5, 1814 letter from Charleston, SC to his sister, Mrs. Sarah Barry, William began the letter with one long sentence, “Dear Sister. It is now nearly 18 months since I have heard from you, so that I almost feel that I have no relations or family in Philadelphia and in fact have not for many years considered myself as belonging to the family.”

A possible cause of the estrangement could be the fact that early in the war, someone offered Captain John Barry “a bribe of 15,000 guineas in gold or 20,000 pounds British sterling, plus a commission in the Royal Navy if he would turn his ship Effingham over to the British. He was promised his own ship under Royal authority which he indignantly refused. In his own words, he ‘spurned the eyedee of being a treater.’” There is great suspicion the person who offered the future commodore this bribe was William Austin, Loyalist, his own brother-in-law.

If so, Captain Barry held no grudge as it was well known he was fond of his brothers-in-law and Sarah’s entire family in general. Such was his nature that he was “intrepid in battle [and] humane to his men as well as adversaries and prisoners”.

During the British Occupation of Philadelphia in 1777, Captain Barry sent his new bride to the household of her sister, Christiana, and her husband, Reynold Keen, in Reading.

With his wife safe, he commanded the ship USS Delaware, a brig sailing under a letter of marque, capturing British vessels in the Delaware River.

Christiana Stille Keen was “heiress-at-law and residuary legatee of Mr. John Stille and inherited the greater part of her father’s land in Moyamensing,” which was later divided between her own children. She married a cousin, Reynold Keen, Esquire, on October 21, 1762.

Life at the Keen estate in Reading was busy with the activities of eight children, many servants and a baby due any day. Reynold Keen was successfully engaged in mercantile pursuits and very wealthy. He and Christiana were immortalized in separate portraits in 1769 by the popular artist, Matthew Pratt, once a student of Benjamin West of London. These portraits can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pierre Eugene du Simitiere included Reynold Keen in his list of 84 families who kept a ‘post-chaise’, a fast carriage for traveling post with a closed body, on 4 wheels, for 2 to 4 travelers, drawn by 4 horses. The Keens also owned a house in Philadelphia, “at 20 South Sixth Street, between Market and Chestnut, two blocks from Independence Hall.”

On October 14th, Sarah’s sister gave birth to her 11th child, who was named Sarah. On November 3rd, Christiana Stille Keen died from childbirth complications. Her husband buried her with an inscription on her tombstone testifying to her “life of piety and benevolence.” The baby, Sarah, was healthy and would grow up to marry James Cooper on October 25, 1812 in Philadelphia. Three months after Christiana’s funeral, ‘a vendu’ of Reynold’s personal goods were ordered by Colonel Henry Haller of Philadelphia and an Act of General Assembly required Reynold Keen to render himself to a judge of the Supreme Court to abide his trial for treason against the new colonial government with his property confiscated. He left his family and Reading estate, “including his young niece, Miss Peggy Stout, in the charge of his sister-in-law, Mrs. John Barry.”

While Sarah was in Reading, Captain Barry “assumed command of USS Raleigh, capturing three prizes before being run aground in action on September 27, 1778.”

By the time Reynold Keen proved his innocence of all charges and his property was returned, 15,000 British troops under General Sir Henry Clinton fled Philadelphia, fearing the arrival of the French fleet.

With her brother-in-law safely returned to his family, Sarah returned to her own home in Philadelphia to face another predicament. Due to the fact that Sarah’s brother, William Austin, joined the fleeing British Army as an officer, his portion of the family fortune had been seized by the Pennsylvania Assembly. Eventually, brother Isaac was able to purchase back his brother’s property for 880 pounds, protecting the Ferry to New Jersey business, buildings and land for future Austin generations.

When Captain William Austin was captured in Yorktown while assisting the raids along the Chesapeake with Benedict Arnold, he wrote to his family while on a New York bound prison ship. Both Sarah and Isaac did not reply. Only his brother-in-law took action.

In a report to General Washington, Captain John Barry added at the bottom, “The Commissary in this Place, Mr Shaw informs me that no prisoners is Exchang’d without your Excellencys orders I have one favour to ask of Your Excellency that is that you will suffer a Captain by the Name of William Austine taken in a Mercht Vessel from [Turtollo] bound to New York, to be Exchang’d or go in on Parole to send a Captain of Equal Rank out for him—he is an Old Acquaintance of mine, and a particular Friend—if your excellency will be pleas’d to grant the above favor, I shall ever Esteem it as a Mark of your FriendShip for Sir Your Excellencys Most Obedt & Verry humble servant John Barry”

William Austin spent the next years in exile, wandering from Nova Scotia to the West Indies, to London and finally settling in South Carolina. He kept up a correspondence with his brother-in-law, often sending small gifts from his travels to John and his sister. In his will, he left his accumulated property to a grand-nephew named Samuel Austin, Jr.

In 1781, Captain Barry returned home to Sarah to recuperate from shrapnel wounds and a severe injury to his left arm, suffered during the capture of both Royal Navy ships, HMS Atalanta and HMS Trepassey, by Barry’s 36 gun sailing frigate, USS Alliance, near Newfoundland, where “grapeshot hit Barry’s left shoulder, seriously wounding him, but he continued to direct the fighting until loss of blood almost robbed him of consciousness.”

It was also with the USS Alliance that Captain Barry and his crew “fought and won the final naval battle of the American Revolution 140 miles (230 km) south of Cape Canaveral on March 10, 1783.”

Sad news arrived from Ireland that Captain Barry’s sister, Eleanor, had died and that her husband, Thomas Hayes, was very ill and probably would not recover. Thomas’ letter asked that they care for his sons, Michael and Patrick. Sarah and John sent for the boys who quickly became the children they always wanted. In 1787, when Captain Barry received an offer to command the merchantman Asia bound for China, Patrick accompanied his uncle, sailing around the world with him, opening commerce with China and the Orient.

With only 1 month left to his office, President George Washington chose John Barry to be issued Navy Commission Number 1, his title thereafter “commodore”. The event was on Feb. 22, 1797 at George Washington’s residence at 190 High Street, “twice a celebration as it was also President Washington’s 65th birthday.”

“Prematurely aged from an arduous life at sea”, Commodore John Barry retired from active duty on March 6, 1801 but remained head of the Navy until his death.

The early 1800s was a heartbreaking time period in Sarah’s life. First, she lost her cousin and brother-in-law, Reynold Keen, on August 29, 1800. He is mentioned in the Federal Gazette, Philadelphia: “Died, on Friday last, after a short illness, in the 65th year of his age, Reynold Keen, esquire, one of the aldermen of this city.”

The next year, dear brother, Isaac Austin, died June 15, 1801. Both Sarah and William inherited equally in his will.

In that same year, Sarah’s beloved adopted son, Michael Hayes, was lost at sea when his ship disappeared in 1801, having been apprenticed to Captain John Rossiter while making many trips to China between 1793 and 1800.

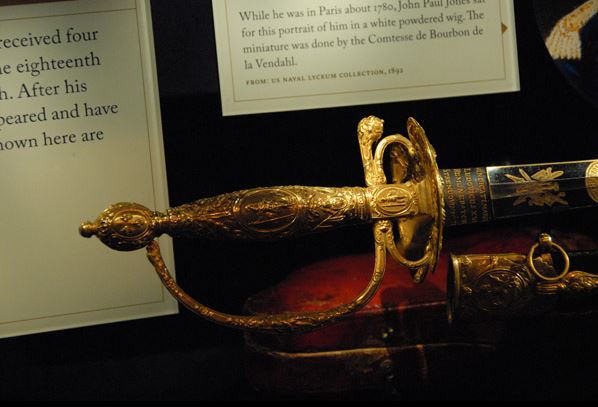

The biggest heartbreak was the lost of her best friend and husband, Commodore John Barry, who died on September 12, 1803, at his country home “Strawberry Hill”, from complications of asthma and gout. He was 58 years old. In his will he left his estate to his wife and adopted son Patrick. To his brother-in-law, William Austin, “as a token of his esteem, he left his “silver-hilted’ sword” which he had carried throughout the Revolutionary War. To his good friend and Sarah’s kinsman, Commodore Richard Dale, he left his “gold-hilted sword“. “This was the sword bestowed by Louis XVI on John Paul Jones, in recognition of his great naval victories.” Commodore Dale was married to Sarah’s cousin, Dorethea Crathorne.

Sarah chose to ease her grief by maintaining close contact with her nieces and nephews and their children. Her main anchors were her adopted son, Patrick Hayes and his wife, Elizabeth ‘Betsy’ Keen. Betsy was the daughter of Sarah’s Uncle William Keen. The Hayes children brought great joy and love to Sarah’s life. They were: John Barry Hayes, Sarah Barry Hayes, Thomas Hayes, Isaac Austin Hayes and Patrick Barry Hayes. The youngest, Patrick Barry Hayes, “served as the Chief Clerk of the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C. 1855.”

Mrs. John Barry died at age 77, at her home, on November 13, 1831 and is buried alongside her husband at Saint Mary’s Catholic Churchyard in Philadelphia. Her portrait now hangs in the offices of the Charles Evans Cemetery Co. in Reading, Pennsylvania. Charles Evans was a prominent attorney who donated the 1st 25 acres and $2,000. to establish the cemetery, leaving a $67,000 endowment for future support in his will. He was the husband of Sarah’s niece, Mary Keen, daughter of Reynold and Sarah’s sister, Christiana. The fact that Sarah’s portrait still holds a place of honor in this modern day office indicates how much she was loved by her family.